Chauncey JuddLongmeadow BrookThe breakfast in the barn was dispatched speedily and in silence; and then Graham, drawing his pipe from his pocket, and lighting it by a flash from his pistol, seated himself upon an upturned bushel measure, and called his men to order for consultation. As to their own movements, they must wait, of course, for David's return before they could decide. Meanwhile another inquiry, of no less importance, was, what should be done with their captive? They could not talk of this very freely in his presence; so one of their number was directed to take him aside to one of the stables, where he would be out of hearing. Their meeting with him was the one misfortune which threatened to upset all their skillfully devised plans. They had so arranged their proceedings the night before, that the alarm awakened by the robbery should be turned in an entirely different direction, and believed that nobody would think of looking for the perpetrators of it in this out-of-the way region. Three of the party belonged here; two others had relations in the vicinity; so that their presence would occasion no suspicion. Graham and Martin might easily be concealed, it was thought, till a convenient opportunity should be afforded for getting away. But now that they had stumbled upon Chauncey, all this went for naught. If he was released, he would disclose their secret and concealment would be impossible. If he was not released, his disappearance itself would create an alarm, in that very neighborhood, which would surely lead to a discovery. The consultation was earnest, but brief. The exigencies of the situation were too obvious to need long consideration. It was very clear that they could not stay in Gunntown, and equally clear that they must not release their prisoner. But what should they do with him? He might be kept in confinement at Mr. Wooster's, or some of the other tory houses, till they could get away; but this would be at the utmost peril of their friends, or whoever should be engaged in it. They might take him along with them; but he would encumber their flight, and expose them every moment to discovery. To every suggestion they could think of, there were insuperable objections. At last Graham, waxing impatient, exclaimed, with an oath,–

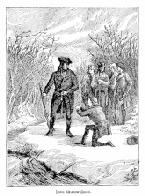

The rest of the party at first stood aghast at this speech. Bad as they were, they were not yet prepared for downright murder. And yet, it was easier to object than it was to find any other way out of the difficulty. Graham was resolute, and, as he was wont to be when opposed, overbearing. They needn't soil their lily hands, he said; he would do the job himself. Let them show him a place where the body might be easily disposed of, and he would soon relieve them of the burden. He only wished he could get rid of the whole Yankee race as easily. At that time the low grounds adjacent to Mr. Gunn's house, now a beautiful meadow, were covered with a thicket of alders and swamp willows. Through this ran the Longmeadow Brook, a good-sized millstream, then, under the melting of the snows and copious March rains, flowing in full banks, and with a swift and strong current. In this thicket a deed of crime like that suggested might be committed without molestation, and any one of the numerous eddies of the brook would afford a place where a body might be sunk out of sight. After a little more demurring from some of the party, it was concluded to take the lad thither. The distance from the barn to the swamp was only a few rods, down a lane, between two stone walls, which served the cattle as a path to water. Calling Chauncey and his keeper from the stable, the men set off down the lane, after reconnoitering the house and road, to ascertain that nobody was in sight. The young man perceived, from the manner of his captors, that something final had been decided on his fate, and began to beg for release. He promised most solemnly that he would keep his meeting with them a secret, but it was without avail. Little was said to him in reply, and the whole party only hurried forward as fast as possible. An open spot was found among the bushes, near where the stream made a deep pool of dark water, flecked with foam from the rapids above. Chauncey was dragged to the brink, and bidden to fall upon his knees, while Graham, with a loaded musket, withdrew a short distance from him.

We cannot attempt to depict the consternation of the poor lad at this announcement. Dark as his forebodings had been, he had not dreamed of this, and the sudden shock almost deprived him reason as well as speech. Rallying again in a moment, he instinctively fell on his knees to beg for his life. He besought them to have pity upon him. He protested that he had no wish to injure them, and repeated the most solemn promises, that if they would release him, he would never reveal their presence in the neighborhood to any human being. He turned to the young men with whom he had been acquainted, and whom he had met at huskings and merry-makings, and entreated them to save him. All seemed in vain. Graham stood immovable, with his watch held forth in his open hand, counting off the minutes as they passed.

The At that moment Henry Wooster sprang forward and clapped his hand over the muzzle. Almost at the same moment both Cady and Scott interposed, rushing in between him and Chauncey. Wooster seized the gun and raised the muzzle into the air. He was, though slender, a powerful young man, and once roused to his full energy, was not to be trifled with. With an oath that outdid for the moment the captain's own, he said,–

Graham was pale with rage. He vented his anger in the most passionate curses. But he saw that he must desist from his purpose, at least for that time. Great as was his influence over men ordinarily, there was a point beyond which they would not go. That point was reached, and he was obliged sulkily to acquiesce. Before the altercation had subsided, a rustling was heard in the thicket near by, and suddenly David Wooster sprang into the open space among them. So saying, he led the way, by paths with which he was familiar, through the swamp and the adjacent fields, till they all arrived safely at Mr. Wooster's. Henry and David kept Chauncey near to them, not only to prevent his escape, but to secure him from harm by Graham, who muttered imprecations on his soul, if he was going to be foiled by a set of white-livered cowards like them. |